A while back and over many years, I developed the habit of channel surfing MSNBC, FNC and CNBC for about an hour while drinking coffee and eating breakfast before heading into my office. At the beginning of the year I moved home and broke the routine, thankfully although inadvertently. I now am sitting at my desk at least an hour earlier and instead of toggling between the MSNBC Trump trash fest, the FNC Biden trash fest and the CNBC schmooze fest, I listen to Bloomberg Radio, hosted by three very smart, very clever, very informed hosts who talk about trade, the economy, etc. and not personalities. I am now caught in the virtuous cycle of happiness and increased productivity. I have never enjoyed my interactions with clients more than now and my business has never been better. I actually feel like I'm working less.

So where am I going with this?

@UHBlackhawk related the story of a WP cadet who was separated shortly before commissioning for a self-reported honor code violation. After going the enlisted route, she eventually returned to WP as the Sergeant Major of Cadets. I commented that stories like that are what keep me optimistic. Since I have replaced my diet of morning news shows I am...again inadvertently, leaving more room in my day and brain for news and stories like that. In particular, I'm interested in news about things that work, not so much one off feel good stories.

So this is my contribution to "Reasons to Feel Optimistic". Hopefully, other posters will join in.

From today's WSJ

By Carine Hajjar

June 2, 2023 2:35 pm ET

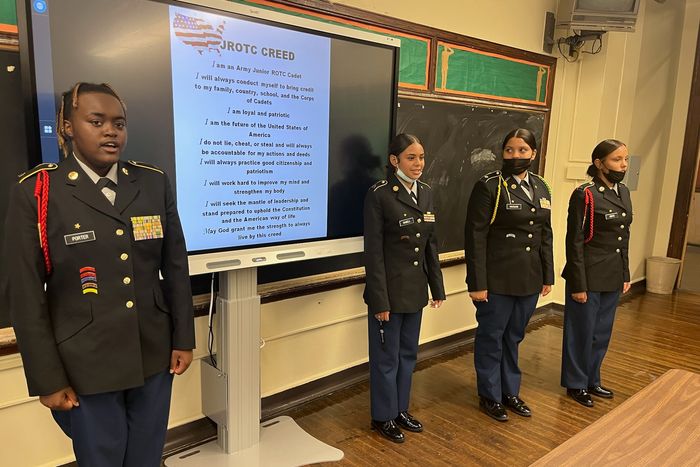

Students at the Philadelphia Military Academy stand next to a photo of the Cadet Creed. PHOTO: PHILADELPHIA MILITARY ACADEMY

Students at the Philadelphia Military Academy stand next to a photo of the Cadet Creed. PHOTO: PHILADELPHIA MILITARY ACADEMY

Philadelphia

Kaheem Bailey-Taylor was leaving a party last August at a cousin’s house in Northern Philadelphia when he heard gunshots. “The suspect started shooting out the door towards us,” he says. Police soon arrived and cleared the house. Mr. Bailey-Taylor followed officers in to assess the situation. Minutes later, he was sitting in the back of a police car applying pressure to a partygoer’s gunshot wounds.

Mr. Bailey-Taylor isn’t a paramedic or a cop; he’s a 17-year-old high-school junior. He is cadet colonel at the Philadelphia Military Academy, where all students are enrolled in the U.S. Army’s Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program. On my visit to the academy, Mr. Bailey-Taylor helps show me around. As we sit in the back of a 10th-grade class on first aid, he leans over and tells me that he used these skills, along with his lifeguard training, the night he helped save the partygoer, one of his classmates.

The class starts like any other, with the buzz of chatty students. It then cuts to silence in unison as a student leader takes his position at the front. Then students recite the cadet creed in one voice: “I will always conduct myself to bring credit to my family, country, school and the Corps of Cadets. I am loyal and patriotic. . . . I will seek the mantle of leadership and stand prepared to uphold the Constitution and the American way of life. May God grant me the strength to always live by this creed.”

Kaheem Bailey-Taylor PHOTO: PHILADELPHIA MILITARY ACADEMY

Kaheem Bailey-Taylor PHOTO: PHILADELPHIA MILITARY ACADEMY

Patriotism, duty and accountability may not be in vogue in most public schools, but here—and in the nearly 3,500 JROTC programs across all military branches nationwide—the values of the cadet creed are a proven formula for success. A 2017 RAND study found that JROTC cadets have better-than-average grades and attendance records and are less likely to drop out than other high-school students. The Philadelphia Military Academy’s graduation rate is 92%; the district average is 75%.

JROTC programs empower students through the chain of command. “Naturally with the ranks that they have, they lean into leadership, and we give them a lot of leeway,” says Principal Kristian Ali, a civilian. My visit to the academy falls on a Class A uniform day. Students wear navy-blue jackets with shiny buttons, festooned with ribbons marking their rank and commemorating anything from a drill-team victory to good grades. Mr. Bailey-Taylor, one of the top-ranking students, spots some cadets who are out of uniform, and tells them to take off their sweatshirts. Respectful of his rank, they comply.

Even the school’s disciplinary system is based on student collaboration. When a conflict arises, cadet leaders are briefed by their peers and decide the best course of action, looping in adults. “It helps kids develop their communication skills . . . their team-building skills,” Ms. Ali says. “All those 21st-century skills that some schools struggle to integrate into the curriculum naturally play out in who we are as a program.”

Beyond skills, JROTC offers the possibility of career development and upward mobility through military service. It’s not mandatory—only around 20% of the Philadelphia Military Academy’s graduates serve—and the skills they learn are also useful in civilian jobs. “There is structure and there are rules and regulations in the world when they graduate,” says Russell Gallagher, the academy’s commandant and a retired Army lieutenant colonel. “We are getting them used to that.” Cadets he has taught are lawyers, nurses, police officers, college professors, military officers and businessmen.

These opportunities are distributed where they are needed most. The RAND study found that JROTC programs are concentrated in high schools with “larger-than-average minority populations” and “economically disadvantaged populations.” All the military branches favor Title I schools—those designated as serving low-income students—when selecting candidate schools for JROTC funding. The Philadelphia Military Academy is a Title I school. All its students qualify for free lunch, and about 90% of students are black and Hispanic.

JROTC generally has bipartisan support, but some lawmakers have raised concerns about its practices and have asked for more oversight. In November, the House Oversight Subcommittee on National Security found that 58 allegations of instructor sexual misconduct had been reported to the Pentagon and substantiated over five years. All the instructors involved had their certifications suspended. The New York Times also reported that some high schools were auto-enrolling students in JROTC, which is meant to be voluntary.

Still, with proper guardrails put into place, even lawmakers calling for more oversight generally support the program. Rep. Chrissy Houlahan (D., Pa.), an Air Force veteran and former chemistry teacher at a Title I school, said in an interview that “we need to be attentive to making sure that [students are] safe and protected” and suggested increasing the number of female instructors. But she also believes that JROTC is an opportunity to “find a community that is rooted in service and discipline.”

Lawmakers see JROTC as a way to help ease the military’s recruitment crisis. The program also instills a sense of civic duty, something often lacking in public education. In the 2020 report, the National Commission on Military, National and Public Service recommended that Congress expand the JROTC program to “enable more students to learn about citizenship and service, gain familiarity with the military, and understand how their own strengths could translate into military careers and other service options.” It also urged “a fair and equitable distribution of JROTC units,” which are underrepresented in rural areas, the mountain states and parts of the Midwest and overrepresented in the Southeast and urban areas.

The program inspires students like Mr. Bailey-Taylor to pursue careers in public service. He says he plans to pursue a college ROTC scholarship, serve as an Army officer, and then work in federal law enforcement to reduce gun crime in his city. “If I won’t stand up,” he says, “nobody else will.”

Ms. Hajjar is the Journal’s Joseph Rago Memorial Fellow.

So where am I going with this?

@UHBlackhawk related the story of a WP cadet who was separated shortly before commissioning for a self-reported honor code violation. After going the enlisted route, she eventually returned to WP as the Sergeant Major of Cadets. I commented that stories like that are what keep me optimistic. Since I have replaced my diet of morning news shows I am...again inadvertently, leaving more room in my day and brain for news and stories like that. In particular, I'm interested in news about things that work, not so much one off feel good stories.

So this is my contribution to "Reasons to Feel Optimistic". Hopefully, other posters will join in.

From today's WSJ

An Officer and a Gentleman—and a High-School Student

The Philadelphia Military Academy offers a chance for career development and upward mobility.

By Carine Hajjar

June 2, 2023 2:35 pm ET

Philadelphia

Kaheem Bailey-Taylor was leaving a party last August at a cousin’s house in Northern Philadelphia when he heard gunshots. “The suspect started shooting out the door towards us,” he says. Police soon arrived and cleared the house. Mr. Bailey-Taylor followed officers in to assess the situation. Minutes later, he was sitting in the back of a police car applying pressure to a partygoer’s gunshot wounds.

Mr. Bailey-Taylor isn’t a paramedic or a cop; he’s a 17-year-old high-school junior. He is cadet colonel at the Philadelphia Military Academy, where all students are enrolled in the U.S. Army’s Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program. On my visit to the academy, Mr. Bailey-Taylor helps show me around. As we sit in the back of a 10th-grade class on first aid, he leans over and tells me that he used these skills, along with his lifeguard training, the night he helped save the partygoer, one of his classmates.

The class starts like any other, with the buzz of chatty students. It then cuts to silence in unison as a student leader takes his position at the front. Then students recite the cadet creed in one voice: “I will always conduct myself to bring credit to my family, country, school and the Corps of Cadets. I am loyal and patriotic. . . . I will seek the mantle of leadership and stand prepared to uphold the Constitution and the American way of life. May God grant me the strength to always live by this creed.”

Patriotism, duty and accountability may not be in vogue in most public schools, but here—and in the nearly 3,500 JROTC programs across all military branches nationwide—the values of the cadet creed are a proven formula for success. A 2017 RAND study found that JROTC cadets have better-than-average grades and attendance records and are less likely to drop out than other high-school students. The Philadelphia Military Academy’s graduation rate is 92%; the district average is 75%.

JROTC programs empower students through the chain of command. “Naturally with the ranks that they have, they lean into leadership, and we give them a lot of leeway,” says Principal Kristian Ali, a civilian. My visit to the academy falls on a Class A uniform day. Students wear navy-blue jackets with shiny buttons, festooned with ribbons marking their rank and commemorating anything from a drill-team victory to good grades. Mr. Bailey-Taylor, one of the top-ranking students, spots some cadets who are out of uniform, and tells them to take off their sweatshirts. Respectful of his rank, they comply.

Even the school’s disciplinary system is based on student collaboration. When a conflict arises, cadet leaders are briefed by their peers and decide the best course of action, looping in adults. “It helps kids develop their communication skills . . . their team-building skills,” Ms. Ali says. “All those 21st-century skills that some schools struggle to integrate into the curriculum naturally play out in who we are as a program.”

Beyond skills, JROTC offers the possibility of career development and upward mobility through military service. It’s not mandatory—only around 20% of the Philadelphia Military Academy’s graduates serve—and the skills they learn are also useful in civilian jobs. “There is structure and there are rules and regulations in the world when they graduate,” says Russell Gallagher, the academy’s commandant and a retired Army lieutenant colonel. “We are getting them used to that.” Cadets he has taught are lawyers, nurses, police officers, college professors, military officers and businessmen.

These opportunities are distributed where they are needed most. The RAND study found that JROTC programs are concentrated in high schools with “larger-than-average minority populations” and “economically disadvantaged populations.” All the military branches favor Title I schools—those designated as serving low-income students—when selecting candidate schools for JROTC funding. The Philadelphia Military Academy is a Title I school. All its students qualify for free lunch, and about 90% of students are black and Hispanic.

JROTC generally has bipartisan support, but some lawmakers have raised concerns about its practices and have asked for more oversight. In November, the House Oversight Subcommittee on National Security found that 58 allegations of instructor sexual misconduct had been reported to the Pentagon and substantiated over five years. All the instructors involved had their certifications suspended. The New York Times also reported that some high schools were auto-enrolling students in JROTC, which is meant to be voluntary.

Still, with proper guardrails put into place, even lawmakers calling for more oversight generally support the program. Rep. Chrissy Houlahan (D., Pa.), an Air Force veteran and former chemistry teacher at a Title I school, said in an interview that “we need to be attentive to making sure that [students are] safe and protected” and suggested increasing the number of female instructors. But she also believes that JROTC is an opportunity to “find a community that is rooted in service and discipline.”

Lawmakers see JROTC as a way to help ease the military’s recruitment crisis. The program also instills a sense of civic duty, something often lacking in public education. In the 2020 report, the National Commission on Military, National and Public Service recommended that Congress expand the JROTC program to “enable more students to learn about citizenship and service, gain familiarity with the military, and understand how their own strengths could translate into military careers and other service options.” It also urged “a fair and equitable distribution of JROTC units,” which are underrepresented in rural areas, the mountain states and parts of the Midwest and overrepresented in the Southeast and urban areas.

The program inspires students like Mr. Bailey-Taylor to pursue careers in public service. He says he plans to pursue a college ROTC scholarship, serve as an Army officer, and then work in federal law enforcement to reduce gun crime in his city. “If I won’t stand up,” he says, “nobody else will.”

Ms. Hajjar is the Journal’s Joseph Rago Memorial Fellow.